“Sharing economy” is an umbrella term with many synonyms: collaborative economy, gig economy, platform economy, peer economy, and “other such” economies. There are nuances to these terms, but each describes an economic interaction that is usually online. To avoid pedantry, the “sharing economy” in this post refer to any economic activity with only these three elements present: peer-to-peer transactions, trust, and the leveraging of underutilized assets.

Peer-to-peer transactions happen directly between user and provider, and are often facilitated by a digital platform. The platform matches and aggregates supply and demand, eliminating the need for an intermediary and reducing costs.

Trust makes these transactions possible. As well as matching supply and demand, digital platforms provide this trust by establishing a moat around its users. The moat are the rules governing each community, which facilitate interactions between strangers. While strangers do not trust each other, they trust their counterpart is motivated to behave because they buy-in to the incentives created by the platform.

In a sharing economy, people buy and sell underutilized assets. These are money (peer-to-peer lending), vehicles, skills, spaces, processing power…really, the possibilities are are as limitless as an entrepreneur’s creativity. Such broad application imbues sharing economy models with transformative force. Ideally, it could be the way to create sustainable and efficient economic value. But, this has often not been the case yet.

The enormous potential of the sharing economy has, nevertheless, inspired the world to think about what could be if a sharing economy takes hold, if it becomes just the economy. Many of these considerations have focused their lens on Africa. Far fewer, though, have considered the impact on a specific African country, like Rwanda

Why Rwanda?

Practically, evaluating how a sharing economy impacts a continent as large and diverse as Africa seems an impossible task. Such analyses cannot help but view Africa as a single monolith and sink into vague generalizations. Narrowing the analytical lens to a single country, on the other hand, allows for nuance, which can yield more insight

Rwanda is the only African country I have lived in and know well. What I observed and experienced while studying in Kigali gives me context to understand Rwanda’s culture and politics. I am no expert, but know enough to believe that Rwanda is a unique candidate for incubating a sharing economy transformation.

Mention Rwanda and the world knows about the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi. But fewer people are aware of Rwanda’s renaissance, its phoenix-like rise since the tragedy. Under the leadership of Paul Kagame, the country has consciously modeled itself after Singapore, emulating the Asian Tiger’s strategy of embracing technology and investing in education to spur the development of a knowledge-based economy. Difficult challenges remain, but there are successes to celebrate: Rwanda is a global leader in women’s political empowerment, its poverty levels are decreasing and economy growing, and the country boasts one of the fastest internet speeds on the continent.

Embracing the sharing economy may further Rwanda’s ambitions. For one, as sharing economy giants look to East Africa to continue their rapid growth, highlighting Rwanda’s ability to market its facility with the sharing economy, coupled with favorable business environment and proximity to Kenya and Tanzania, could attract investment from Chinese and western unicorns.

Private sector investments would alleviate Rwanda’s reliance on aid funding. Furthermore, developing and hosting sharing economy businesses would diversify Rwanda’s predominantly agricultural economy, a key step if it is to succeed in its goal to be a middle-income country. Research suggests these companies also increase accessibility to goods and services and help integrate marginalized groups into mainstream economic activity. Irembo, a Rwandan company making over 80 government services accessible online, is a poetic example of such benefits.

Can Rwanda Integrate a Sharing Economy?

Rwanda possess intrinsic characteristics that make the integration of a sharing economy plausible. Chief among these is the presence of a non-digital sharing economy where neighbors ride to work together, families help each other out with groceries, and neighborhood money pools provide essential capital. In markets, a system of barter and debt extends capital without complex accounting or credit checks.

The lubricant for sharing is trust. Its foundations in Rwanda are numerous, but its consequences are clear: more options at no cost. The opportunity for Rwanda is scaling trust beyond people’s immediate community to multiply these benefits.

A digital platform connecting producers and consumers, intrinsic to sharing economy businesses, effectively scales trust. Platforms provide common rules for an interaction between strangers and trust mechanisms, such as user reviews, that incentivize transactions to stay on the platform. When everyone buys in, which is easier when people are comfortable sharing, the platform benefits from a network effect, its pull and incentives becoming stronger the more it is used.

Platforms provide this common playing field with digital technology, so they are able to scale the benefits without investing in economies of scale. A mobile app can be downloaded endlessly without extra cost, while user verification requires companies to write code only one time. Platform businesses also do not need brick-and-mortar infrastructure to ensure their system works, making such models especially appealing in Rwanda where access to capital is limited.

When scaling trust opens opportunities to leverage underused assets, individuals with entrepreneurial spirit are needed to take advantage. Rwandans seemingly have this spirit in ample supply: entrepreneurship is taught in schools, encouraged by friendly policies, and modeled by creative leadership. The country boasts you can start a business there in less than 6 hours and consistently ranks as the second best African country according to the Ease of Business Index from the World Bank. Rwanda also seizes any opportunity to market itself on the world stage, most recently sponsoring Arsenal FC, a Premier League team with worldwide viewership, to encourage tourists to “Visit Rwanda.”

Rwandans themselves are resilient, resourceful, and familiar with the dynamic labor demands of the sharing economy. Their resurgence since 1994 is proof enough, but even today, when steady employment is hard to find, Rwandan ingenuity is evident in how people string together gigs to make a living. Whether by peddling a bike taxi or providing a mobile charging station, many Rwandans manage multiple income-flows, a skill increasingly necessary elsewhere as the full-time work hegemony faces disruption.

A Digital Petri Dish

The more familiar and comfortable people are hustling in this environment, the greater potential for fruits of the sharing, because people have access opportunities provided by unique flexibility and demands of the sharing economy. Even without a robust sharing economy domestically, Rwandans’ ingenuity may be an advantage in the global gig economy, where platforms make it easier for freelancers and companies to perform engagingly regardless of physical location.

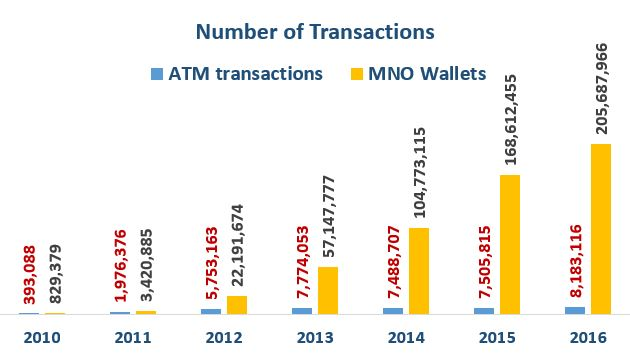

A rapidly evolving digital infrastructure is one of Rwanda’s greatest assets in becoming a sharing economy petri dish. The fast and expanding internet coverage earlier mentioned in addition to mobile penetration and digital currency; i.e. money are growing economic activities in Rwanda. Though the ratio of electronic retail payments to GDP was a modest 21.6% in 2016, the statistic belies the country’s ambition. One of Rwanda’s goals, as outlined in the country’s development manifesto, is to become a cashless economy by 2020. This goal will not be reached by next year as predicted. However, its mere existence ensures that the Rwanda continues to build digital infrastructures and systems to support a transition from cash circulation to cashless economic transactions.

Mobile communications infrastructure and internet connectivity are the key digital tools towards a digital sharing economy because they provide the means by which businesses can bypass chronic pain points of central banking systems. These tools are virtually non-existent in Rwanda. By some estimates, SME in developing countries have an unmet financing need of $5.2 trillion. Sharing economy businesses can overcome financial hurdles much faster than traditional businesses because, as aggregators, they do not need to amass their own inventory or provide any services beyond the platform. Lesser capital needs makes entrepreneurship particularly suitable business ventures in under-financed economies.

The extent to which Rwanda’s affordances support the integration of a sharing economy depends largely on how much companies can take advantage of these economic opportunities. Expansions from sharing economy giants into East Africa will certainly impact Rwanda, but the extent of this impact, at least in the short-term is less. Growth obsessed companies may forgo Rwanda’s small economy for the mouthwatering big markets in Tanzania and Kenya. Moreover, these companies are targeting western consumers, who are more likely to own a smartphone and use credit cards than their East African counterparts. Adjustment will take time.

Therefore, homegrown sharing economy business can be the quickest way to leverage Rwanda’s affordances. Rwandan entrepreneurs understand the underlying social fabric, especially the nature of trust within communities, and the potential and limitations of digital infrastructure. They have been steeped in the country’s post-1994 ideology, which is dogmatically collective, youthful, and embraces change and modernism. Equipped with such worldview, and maturing at a time of growing access to finance, Rwandan entrepreneurs are poised to innovate the sharing economy.

And they may do it. The early effects of business-friendly policies, entrepreneurial attitudes, and favorable demographics on startup activity are promising. Government sponsored co-working spaces attract young people with free internet and keep them coming with a series of speakers and skill development workshops. The next generation of Rwandans are responding, building digital tools for improving education, transportation, and agriculture. If, more sharing economy businesses become part of this portfolio, innovation is certain to emerge out of the Land of a Thousand Hills.

Thomas Rocca is an economic development enthusiast, who generously agreed work in partnership with Think Africa ry. The blog on innovation and business development in Rwanda is a courtesy of Mr. Thomas Rocca and his interest in the activities of Think Africa.

Such concrete and holistic approach on Rwandan current economy growths’ process wouldn’t let me stay quite! You have said it all and well said. Thank you.